In his autobiography, Jean-Bertrand Aristide recalls the night of Haiti’s first free and fair elections, held on December 16, 1990, following three decades of dictatorship. On that day, Haiti’s poor majority struck a blow for justice, morality and democracy by electing Aristide, candidate of Haiti’s Lavalas people’s party, President by a landslide:

Never will I forget that night of December 16th! It was Dec. 16, 1990, an almost cool evening in the Caribbean winter: an electric evening, even if the electricity, like so many other things in Haiti, was often lacking. In fact, it was an evening glowing with the hope and the fervor of a whole people. Even if we did not really doubt it, we waited. We awaited the results of the first free elections in our history. All day long Haitians had been voting in overwhelming numbers. How many people had whispered or shouted it to me: dodging bullets, skimming over walls, on all fours or with heads held high – ‘we are going to vote.’ Even if the candidate is called Titid, his affectionate nickname, the people had for the first time the feeling of voting for themselves, for their own demands, for their own vision of the world. From the springs of many organizations, from an infinite number of rivulets had been born this torrent, ‘lavalas‘ in Creole, that would sweep away the loathsome debris of successive dictatorships.

At times there were thousands waiting to vote on the borders of the slums, standing in line, sometimes in whole families, with patience and beauty. Beauty? Indeed, because even at the worst times the Haitian people have cultivated this sense with zeal and extraordinary perseverance. Sometimes they waited for hours in the blazing sun, all my illiterate brothers and sisters, outside their miserable huts. They waited as long as necessary, armed with their little cards marked “NS,” the mark for the Lavalas list, colored as red as a prize rooster. Even in the residential districts of Petionville, several kilometers outside Port-au-Prince, farther from the unhealthful miasmas of the central city, we were winning. The immeasurable crowds that had gathered throughout the campaign were witnesses. Never in the memory of black people had anyone seen sixty thousand people at Cap Haitien, the second-largest city, in the north of the country.

There was hope in their faces, and success was flashing forth every moment, from the bottom of the ballot boxes. Still, for five years, from Namphy to Avril, the generals assisted by the Tontons Macoute and corrupt politicians had again and again stolen the popular victories: by delaying elections or massacring the voters. They had clothed themselves in the garments of democracy in order to laugh at international opinion, while wielding the machete or the revolver against genuine democrats. They spoke of elections, but whispered that an illiterate nation did not have the necessary maturity to vote. And yet there had never been a genuine literacy campaign or even an attempt at schooling: only one child in three ever goes to school. The vicious circle of ignorance and oppression could perpetuate itself ad vitam aeternam!

But this time the balloting took place without a major incident, and the hundreds of international observers and dozens of journalists appeared to be armed against fraud or intimidation. There was a group of us, friends, who were waiting, imagining what Roger Lafontant, a leader of the Duvalierists, and his associates could be preparing. At eleven o’clock the telephone rang one more time: “We cannot proclaim the official results, but the numbers are such that, practically speaking, you have been elected. Elected!”

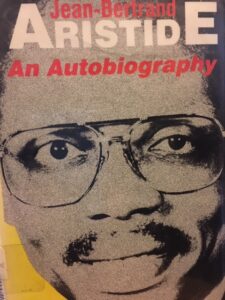

– from Jean-Bertrand Aristide: An Autobiography