Haiti Action Committee is honored to share the keynote address given by Haiti’s former First Lady Mildred Aristide at the April 8th, 2025 Samuel Dash Conference on Human Rights: Truth, Solidarity and Repair. The conference was co-sponsored by the Georgetown Law Human Rights Institute and the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti. The focus of this year’s conference was “Haiti and the Global Movement for Reparations.” We urge you to share this presentation widely. Watch the video recording here: Mildred Aristide: Haiti and the Global Movement for Reparations

SAMUEL DASH CONFERENCE ON HUMAN RIGHTS

Truth, Solidarity and Repair

Haiti and the Global Movement for Reparations

April 8, 2025

Good morning.

I would like to thank the Georgetown Law Human Rights Institute for centering this year’s Samuel Dash Conference on Haiti.

I would like to thank the Georgetown Law Human Rights Institute for centering this year’s Samuel Dash Conference on Haiti.

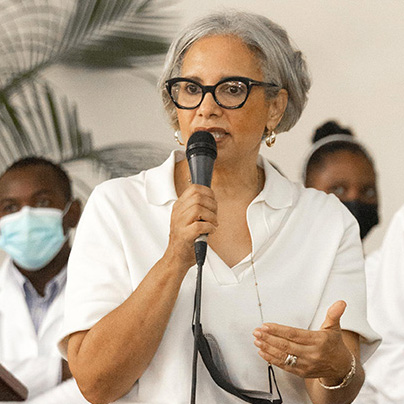

Thank you Elisa Massimino for this invitation – knowing that my presentation would have to be virtual: I’m coming to you this morning from our campus auditorium at UNIFA, the university that President Aristide founded in 2002, located in Tabarre, just outside the capital Port-au-Prince.

A special thanks to Brian Concannon, co-founder of the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti, friend of over 25 years, colleague to Mario Joseph, that most courageous defender of human rights in Haiti – so needed in this moment – of whom he spoke so eloquently. Your collaboration with Georgetown Law brings this important legal and moral issue of reparations for Haiti to a new generation of law students. It empowers them to join the global movement for reparations for all formerly enslaved and colonized people.

Since November 11th travel to and from Haiti has become difficult. A shooting at the capital’s airport triggered an immediate ban by the US government on all US flights. Our border with the Dominican Republic has been closed for over a year. International travel from Port-au-Prince involves either a 6-7 hour bus ride to Cape Haitian or a 40-minute helicopter shuttle that can run up to 2,500 US dollars.

From there a local airline flies to Miami – at a significantly increased ticket price.

The country is facing an extraordinary situation. The capital (and some provinces) are under siege by heavily armed paramilitary forces. They are responsible for an untold number of killings, kidnapping, rapes, acts of arson and pillage. Entire swathes of the city have been abandoned. Hospitals, schools, businesses destroyed. Families displaced from homes, living in makeshift settlements. A total upending of everyday life. Food production has plummeted, while blocked roads prevent agricultural products from making it to markets. Prices of basic staples have more than quadrupled. Alarming signs that hunger and famine are rising. Access to basic services like education, healthcare, sanitation – fragile in better times – are non-existent now in a growing number of areas. Cases of cholera are increasing. And, given the uncertainty surrounding the fate of hundreds of thousands of Haitians living in the US – whose remittances home are a lifeline – the situation looks to worsen.

A legacy of 33 violent coup d’états – the most recent in February 2004 – a 32-year dictatorship, a repressive army, corruption, fraudulent elections, and foreign interference has rendered Haiti’s system of governance weak, resulting in the current predicament: A provisional presidential council unable to stabilize the country or restore security – 1,000 Kenyan police officers, notwithstanding.

I began my remarks with the dire conditions on the ground as the necessary backdrop to today’s discussions to show the scope of the harm and critical need for relief.

First I’ll highlight the trajectory of the debt – as I have no doubt that the full history of this most quintessential of odious sovereign debts will be expertly recounted today.

Then I’ll share what mobilization for reparations was like in Haiti after April 7, 2003, when President Aristide became the first president to request reparations and restitution from France. A mobilization that went beyond the demand for monetary redress and was animated by a spirit to honor the sacrifices made by the country’s founders and move towards national repair.

And I’ll close with reflections on how despite the present national trauma our UNIFA students maintain the ethos of this mobilization and the commitment to repair the nation.

At the start of the Haitian revolution in 1791, the population of enslaved Africans was estimated at 500,000; while there were only about 30,000 Europeans on the island. To compensate for being so greatly outnumbered colonial masters exerted unimaginable violence.

At the price of this horror, Haiti was France’s richest colony. Nearly 20% of the French population owed its livelihood to the trade in or work of, African enslaved people in Haiti.

After their defeat in 1804, France was determined to recapture this wealth.

In 1817 a French spy named Medina was arrested by Henri Christophe in possession of formal instructions outlining the intended consequences if Haiti did not submit to French authority: Blacks would be re-enslaved and the island purged of anyone that posed any danger to maintaining this order.

The ordinance signed by King Charles X and presented to Haiti’s President Boyer was in exchange for formal recognition of Haiti’s independence. In return France demanded that Haiti pay 150 million gold francs and reduce by 50% the tariffs on all French imports. The indemnity was 10 times Haiti’s then national budget. To make the first payment, Haiti was forced to take a loan from a French bank, hence the creation of a double debt.

Boyer declared the indemnity a national debt payable by all Haitians. But in reality, new onerous taxes imposed on agricultural products, principally coffee, hit the peyizan – poor farmers in the countryside – hardest. A brutal Rural Code was enacted to maximize production by strictly controlling the lives of the peyizan. Growing misery in the countryside prompted revolts in 1842 that resulted in some reforms to the constitution and ultimately, Boyer’s fall. Although the Code was rescinded in 1843, it laid the groundwork for an enduring color/class divide akin to apartheid. People outside the capital were called moun andeyo – people outside. Their births certificates – like that of my husband born in the South in 1953 – stamped with the word: peyizan – peasant.

Compare the misery in 19th century rural Haiti to the documented boon to the French economy happening simultaneously and precisely as a result of the extortionary debt.

Through the late 19th and early 20th century, there was unending political tumult as foreign loans were consolidated, refinanced and reissued. Successive governments, many corrupt, attempted to meet payments, failed, were overthrown, exiled and replaced. At one point, 80% of the government’s resources went to debt service. The National Bank of Haiti established in 1880 was in fact a for-profit, privately owned French bank in Haiti created explicitly to control Haiti’s finances to more efficiently extract money from the economy.

Simmering tension between Europe and the US to control Haiti, and more importantly those moneymaking loans, ended in 1914 when eight US marines soldiers walked into Haiti’s national bank and seized 500,000 dollars worth of gold reserves. This gold was deposited directly in the National City Bank of New York. Nine months later the US occupation ensued. US marines and a newly created Haitian army made a spectacle of violently quashing all potential opposition. City Bank took control of Haiti’s so-called national bank and remained in charge 14 years after the US occupation officially ended in 1934. It made sure that Haiti paid every last penny of the 1825 indemnity and a succession of government loans – of little to no benefit to the country – but of great benefit to American investors.

My father, born in 1929, could still sing the jingle that he and classmates were taught at school as they threw coins into a collection basket to help pay the last installments on final iterations of the indemnity.

So that’s a quick overview of the indemnity through to the early mid 20th century when the remnants of the debt were finally paid.

Without a doubt, before April 7, 2003, the story of the debt was common knowledge to Haitians. It was taught in schools and the story recounted across many kitchen tables in the Haitian diaspora, including mine. There was general consensus among Haitian scholars that the indemnity and the ensuing loans to pay had set Haiti on a course of financial crisis that was the principle factor in its underdevelopment.

But until April 7, 2003, when, in a speech commemorating the 200th anniversary of founding father Toussaint Louverture’s death, President Aristide called on France to pay restitution for the 1825 indemnity, the issue of reparations had never penetrated the political realm.

President Aristide entered the realm of politics in the 1980s. A former Catholic priest and adherent to liberation theology, he was a leading figure of the democratic movement that ushered the end of the Duvalier dictatorship in 1986. In 1990 he become Haiti’s first democratically elected president. There was hope. The flight of refugees to Miami stopped, thousands of Haitians who fled Haiti under Duvalier returned and the minimum wage was set to increase. Aristide’s goal was at once simple and at the same time profound: To move the country from misery to poverty with dignity.

Fast-forward, to 9 months later, an army–led coup d’état brutally ended Haiti’s experiment with democracy. Between 4-7 thousand people were killed; tens of thousands forced to the high seas; 300,000 internally displaced and countless more victims of illegal arrests and tortures. Aristide was forced into exile.

After 3 long years, he returned to finish the remaining 15 months of his term. He demobilized the Haitian army, established a civilian police force and set up a truth and reconciliation commission to examine the crimes committed during the coup. And in 1996, for the first time there was a democratic transition of power in Haiti.

Five years later, President Aristide was re-elected with over 90% of the vote. A clear mandate to continue the work begun in 1991. Under two successive administrations led by his Lavalas political movement, more schools were built between the years 1994 and 2000 than in the previous 190 years. But forces within the international community and their financed partners in Haiti stood in opposition to his policies. Emblematic of this opposition was the block on government access to international loans. Like, for example a 54 million dollar loan awarded since 1998 to improve the crumbling water system. The devastating health impact of this blocked loan was investigated and report by Partners in Health in 2008. Destabilizing the Haitian government trumped giving lifesaving service to the population. Instead, money flowed freely and abundantly to groups whose sole mission was to undermine – through violence and propaganda – the democratically elected government.

It is in this moment, as the government prepared to celebrate the January 1, 2004 bicentennial of Haiti’s independence that the call for restitution and reparation was made. The amount demanded – $21,685,135,571.48 – was the present day value of the indemnity paid by Haiti, as calculated by the government’s Restitution Commission. Ira Kurzban, commission member, dear friend and then legal counsel to the government will elaborate on the commission’s legal and diplomatic strategy in this afternoon’s panel.

To be clear, the restitution campaign did not replace government action to improve the lives of Haitians. In those 10 months between April 2003 and the coup d’état of February 29, 2004, the government finished construction on schools, public plazas and a fully equipped, modern university teaching hospital was inaugurated.

A case of showing by example, what reparatory justice looked like.

A popular singer of the rasin – or roots – genre of Haitian music was picked to set the cultural tone of the campaign. And because rasin music runs deep in the country’s culture, honoring the spirituality of Voudou, the song’s instant popularity was assured. It was the soundtrack to rallies and meetings. Schools organized debates on restitution and challenged students to deepen their understanding of history. Public radio and television broadcasters hosted public lectures by subject experts and scholars. I remember that on a visit to one of many new literacy centers at a public market, President Aristide wrote the word RESTITUTION on the chalkboard and led a discussion among the market women/students around the theme. The words reparation and restitution appeared on bumper stickers, shopping bags and walls across the city. The government launched a national competition inviting artists to render in their chosen creative form, an interpretation of restitution. The creator of a sculpture titled Soif de paix – thirsty for peace – was one of the first early winners.

I got swept up in the power of this history and how people internalized this sense of reparatory justice. It motivated me to start my own restitution project: a pamphlet tracing the history of the debt. I worked with staff at the National Library to locate primary source material, out of print books, and had access to archival documents gathered by the Restitution Commission. I photographed entries from the restitution competition when the pieces were brought to the National Palace and included several in the pamphlet. The works were to be curated and displayed at a new Museum of Restitution.

But then came the coup d’état. The pamphlet was never published, the art destroyed, the museum locale set a blaze in the early hours of the coup. And within weeks of being installed, the de facto prime minister traveled to France to apologize and formally withdraw Haiti’s request for restitution.

I refer you to the 2022 New York Times series titled “The Ransom”, that concludes with an admission that the February 2004 coup was “orchestrated against Aristide … and that his removal was probably a bit about his call for reparations from France.” Oh, and that the $21 billion in losses to Haiti was actually closer to $115 billion.

On the night of February 29, 2004, Titid and I were shuttled to a French military base in Bangui, capital of the Republic of Central Africa. After two weeks Congresswoman Maxine Waters, the late Randall Robinson, and Ira Kurzban boarded a chartered plane, flew to Bangui and negotiated our release. They accompanied us to Jamaica where we reunited with our two daughters. After 3 months President Thabo Mbeki invited us to South Africa where we spent 7 years in exile.

When we returned to Haiti in March 2011, Aristide immediately set out to reopen UNIFA. The challenges were many. Students had been kicked off campus and the university transformed to military barracks for the foreign troops that had come to Haiti. The residential campus was settled by families displaced by the devastating January 2010 earthquake. President Aristide was undaunted. He assembled a staff, reached out to former UNIFA teachers, Haitian medical professionals, local and international supporters, and in October 2011 we re-opened with 126 students – 63 women and 63 men.

Today we have 4,076 students studying across 8 disciplines. And since the university’s reopening 1,904 doctors, lawyers, nurses, dentists, engineers, physical therapists, and agronomists, have graduated from right here on this stage.

Our students confront and surmount indescribable adversity to be here. They have watched many classmates opt to leave the country and have wrestled with this question. But have stayed. Finding not only a career path, but importantly, a sense of community and purpose. Working together on group research projects; planting corn, raising chickens and harvesting honey on our student farm; singing with the University choir; organizing mobile clinics and blood drives for the community; lecturing at area high schools; bringing medical relief to communities impacted by a deadly hurricanes in the South; participating in our annual Celebration of Dignity.

Engagement in a common and collective pursuit to change and rebuild Haiti.

This idea crystalized last month when again from this same stage, a group of our medical residents were invited to speak at our weekly lecture series. These are some of our brightest med school graduates enrolled in the residency program at our UNIFA teaching hospital on the other end of campus. After describing her pediatrics training, one resident concluded by encouraging students to stay strong and to persevere – precisely because the conditions in the country are so difficult. “Nous avons une dette envers ce pays.” She said, “We have a debt to this country.”

This, I thought, is what reparatory justice looks like. Advocating for what is just and right – restitution and reparations for all formerly enslaved and colonized people – while at the same time taking action to repair Haiti.

Thank you